When the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) broke out, a group of Mormons took the opportunity to form a battalion that would be sent west to lands they hoped to settle after the war. After a grueling 1,900-mile march from Ft. Leavenworth through present-day Kansas, New Mexico, and Arizona, the battalion arrived in southern California and was instrumental in the securing of posts for the US along the way. The Mormon Battalion was disbanded in July of 1847 in Los Angeles and many headed back to the new Mormon Settlement in Utah.

But some reenlisted, and when the war ended, rumors of gold strikes farther north in California had made it to Los Angeles. Rather than returning to Utah, many of the men remained behind to seek their fortunes in the gold fields.

A Familiar Problem

It was a familiar situation for prospectors in the Old West. After working tirelessly to extract gold dust or nuggets, they needed a way to make it spendable. Assayers and banks, if they were even available, would charge high fees to process and convert the metal locally. Some might even offer to send it to Philadelphia for coining into official US currency, an unattractive proposition given the time and costs involved. Businesses would undervalue raw gold or overcharge for goods and services because of its unknown purity and the difficulty of handling it.

Keeping It in the Family

Rather than trusting their fates to local businesses, many of the Mormon prospectors chose to take their bounty back to Salt Lake where they were confident it would be handled ethically. That led to large amounts of gold arriving at the Mormon settlement, and its leader, Brigham Young, needed a way to process it.

He turned to a man named John Kay, who had learned pattern-making at his uncle’s foundry in England to design a new Mormon coinage.

One side of the simple coin showed a Phrygian cap with an all-seeing eye below surrounded by the inscription “To The Lord Holiness.” The other showed two hands clasping encircled by the initials “GSLC” and “PG” standing for Great Salt Lake City and Pure Gold along with the denomination. The year was shown below the clasped hands.

The new issues retain the same clasped hands and all-seeing eye symbols as those designed in 1848. The words “Pure Gold” represented by the initials “P.G.,” and the letters “G. S. L. C.” were added for “Great Salt Lake City.”

Trial and Error

But Kay had no experience in coin-making. He first struck ten-dollar coins, but the crucibles broke. New crucibles arrived in September 1849 and production resumed on gold coins in the same $2.50, $5, $10, and $20 denominations as official US coinage. Lacking a skilled assayer, the new Deseret Mint relied on the widely accepted “relative fineness” of native California gold to determine the purity of the gold they coined.

But “relative fineness” is, well, relative and although the coins were minted in good faith at US prescribed weights, the gold shipped back to Utah fell short of official purity standards and crude manufacturing caused weights to vary. According to an assay of a $20 Mormon gold coin at the New Orleans Mint in 1850, it was lower in purity (.892 vs the .900 standard) and underweight by roughly 20 percent. Further assays confirmed the deviation from standard of various Mormon denominations.

Needless to say, this led to accusations and devaluation of the coins in commerce, but no intent to defraud was ever proven. More likely the errors were due to lack of sophisticated assaying and minting equipment at the Deseret Mint.

Collectability and Value of Mormon Gold Coins

While the Mormon coins may have been worth less than their weight in gold in the mid-19th century, that’s certainly not the case today.

An estimated 70,000 Mormon gold coins were made but very few survive today, most having been melted down for their metal. The $2.50 denomination was the most numerous coin minted, with quantities falling as the denominations increased in value.

An 1849 $2.50 coin graded MS63, the best of 39 known to survive, sold at auction for $235,000 in 2014. Even heavily worn samples are valued at $35,000 and up.

The five known 1849 $10 coins start at $325,000 for a VF15 grade and the only known AU55 sample is estimated by PCGS to be worth $800,000. A slightly less rare $20 coin might bring $675,000 if it were to come to market.

Other $5 coins with slightly different patterns were struck in 1850 and 1860, and while there are more survivors than the 1849 mintage, they still command six-figure prices in Mint State.

- $1 Silver Certificates & Notes

- $2 Silver Certificates & Notes

- $5 Silver Certificates & Notes

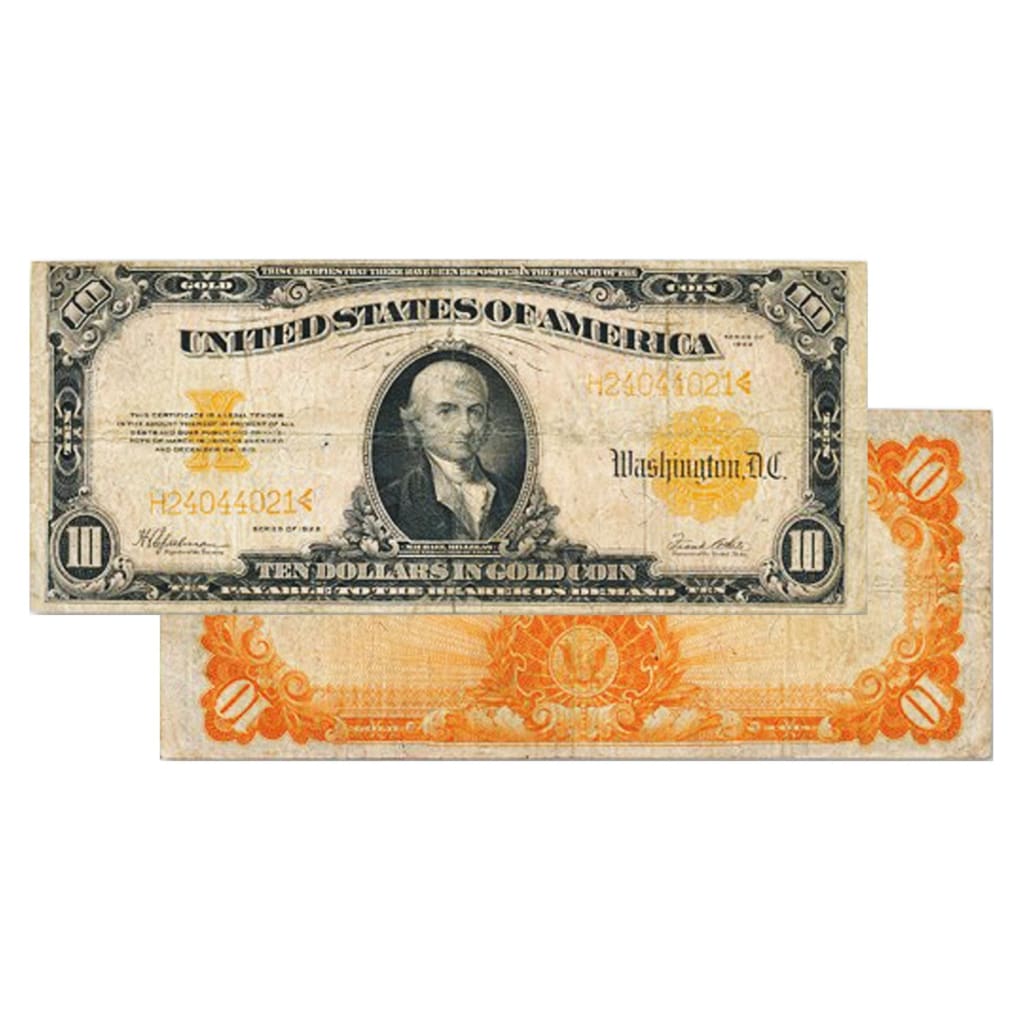

- Gold Certificates & Notes

- North African Federal Reserve Notes

- Hawaiian Federal Reserve Notes

- Large Size Notes

- $20-$1000 Gold Certificates & Notes

- Confederate Banknotes

- Cull and Low-Grade US Paper Money

- Uncut Currency Sheets

- Wholesale Banknotes

- Display All U.S. Paper Money